Synopsis/Details

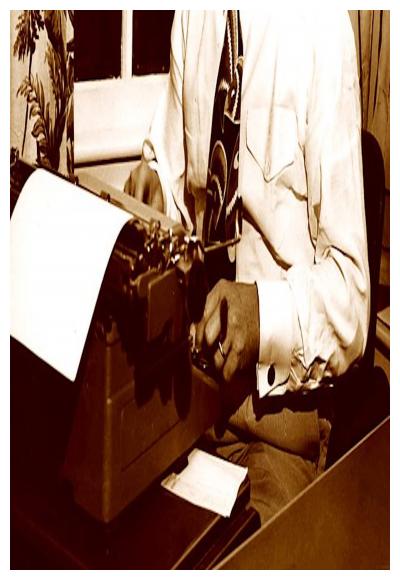

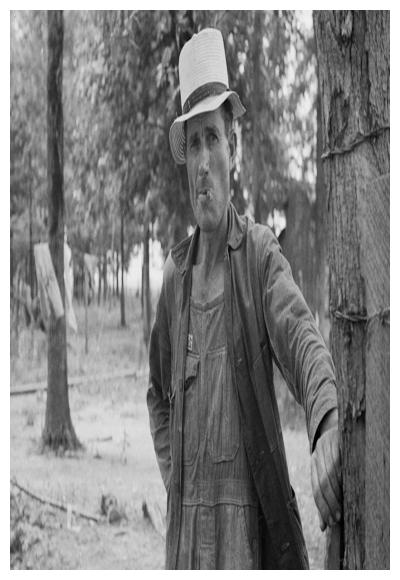

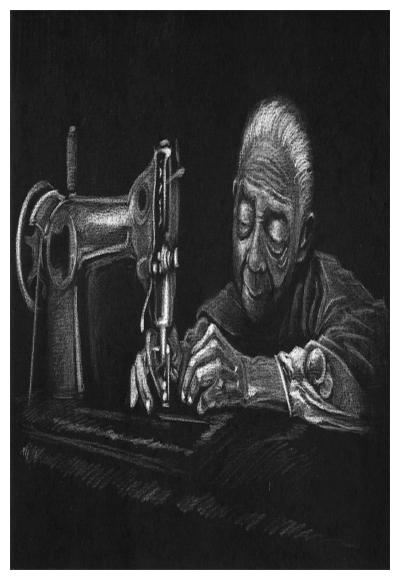

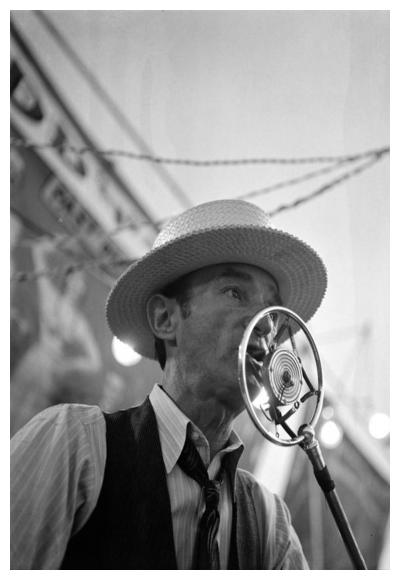

Conley Pace is the Sunday Editor of the "New York Eclipse". The kind of reporting practiced by the "Eclipse", whose offices are located atop an immense building on Broadway, seems to be a parodic equivalent of the sensationalist yellow journalism made notorious by Joseph Pulitzer of the "New York World" and William Randolph Hearst of the "New York Journal" in the latter part of the nineteenth century. The "Eclipse" features disasters, scandal, and horror stories. One of the pieces Pace chooses to titillate the depraved readers of his newspaper is illustrated with a half-page drawing of a deformed baby born in Massachusetts: an infant who possesses just one eye and, instead of arms, merely a pair of fin-like hands growing from its chest. One of the people Pace throws out of his office is a middle-aged Greek munitions inventor, on crutches, who seeks the help of the "Eclipse" in promoting his latest weapon: a large gun with a range of forty miles.

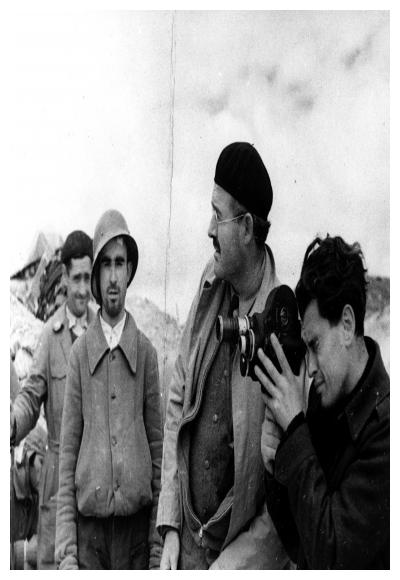

Several weeks after the publication of the article on the deformed baby, Conley Pace advises Sturgeon, the proprietor of the "New York Eclipse", that he would like to go on vacation to Greece to report on the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. (Pace’s boss proposes instead that the newspaper recruit a battalion of men to go to Cuba and fight the Spaniards under its own flag—the "Eclipse" flag [as opposed to the flag of the United States, in what would become the Spanish-American War of 1898].) Sturgeon observes that war correspondence is not very restful, and may even be an idiotic way to take a vacation, but he accedes to Pace’s request for “active service.”

On the steamship to Liverpool, Conrad Pace encounters Nora Black, a comic-opera performer with whom he had been previously involved romantically. She is on her way to London for a theatrical engagement. Nora, an independent, sensuous woman, obviously still cares for Pace—the kind of man she really likes (one she cannot control), she says. But he is impervious to her blandishments, or those of any other woman, for that matter.

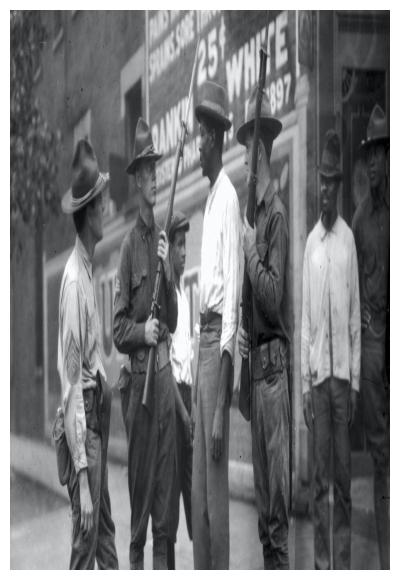

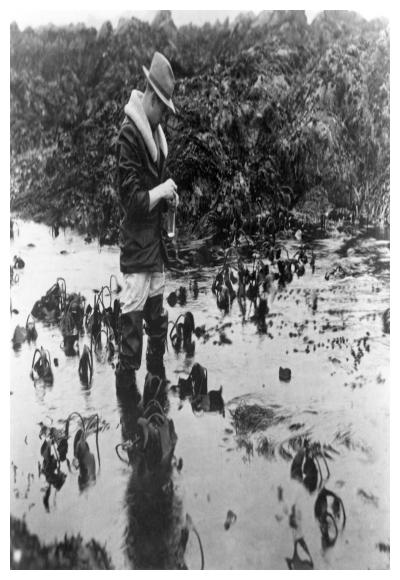

From Liverpool, Conley Pace travels by train to London, by ferry from Dover to Calais, and then again by train to Athens. There he obtains a guide and supplies and attempts to journey, by rail, boat, coach, and foot, to where the military action is: in Arta, Greece. Walking along the road there, Pace and his guide confront a disturbing portent of the horrors of war—indeed, of the discord of life—when they come upon a group of soldiers watching the burial of a dead Turk (who stands in direct contrast to the barking dog atop the correspondent’s earlier stagecoach to Arta). Pace goes to look at the man’s little clay-colored body, and at that moment a snake runs out from a tuft of grass and wriggles wildly over the ground, toward the corpse. The Greek Guide screams out but one of the soldiers quickly puts his heel upon the head of the reptile, which flings itself into an agonizing death-knot.

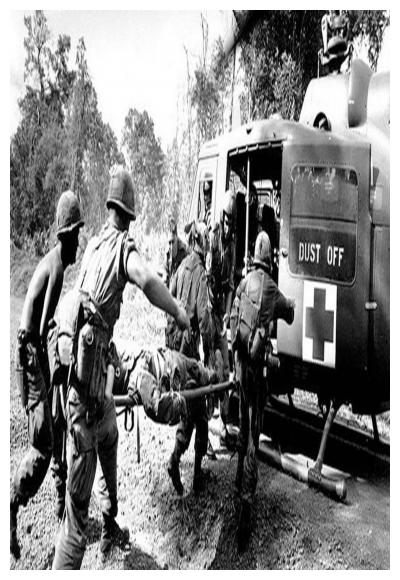

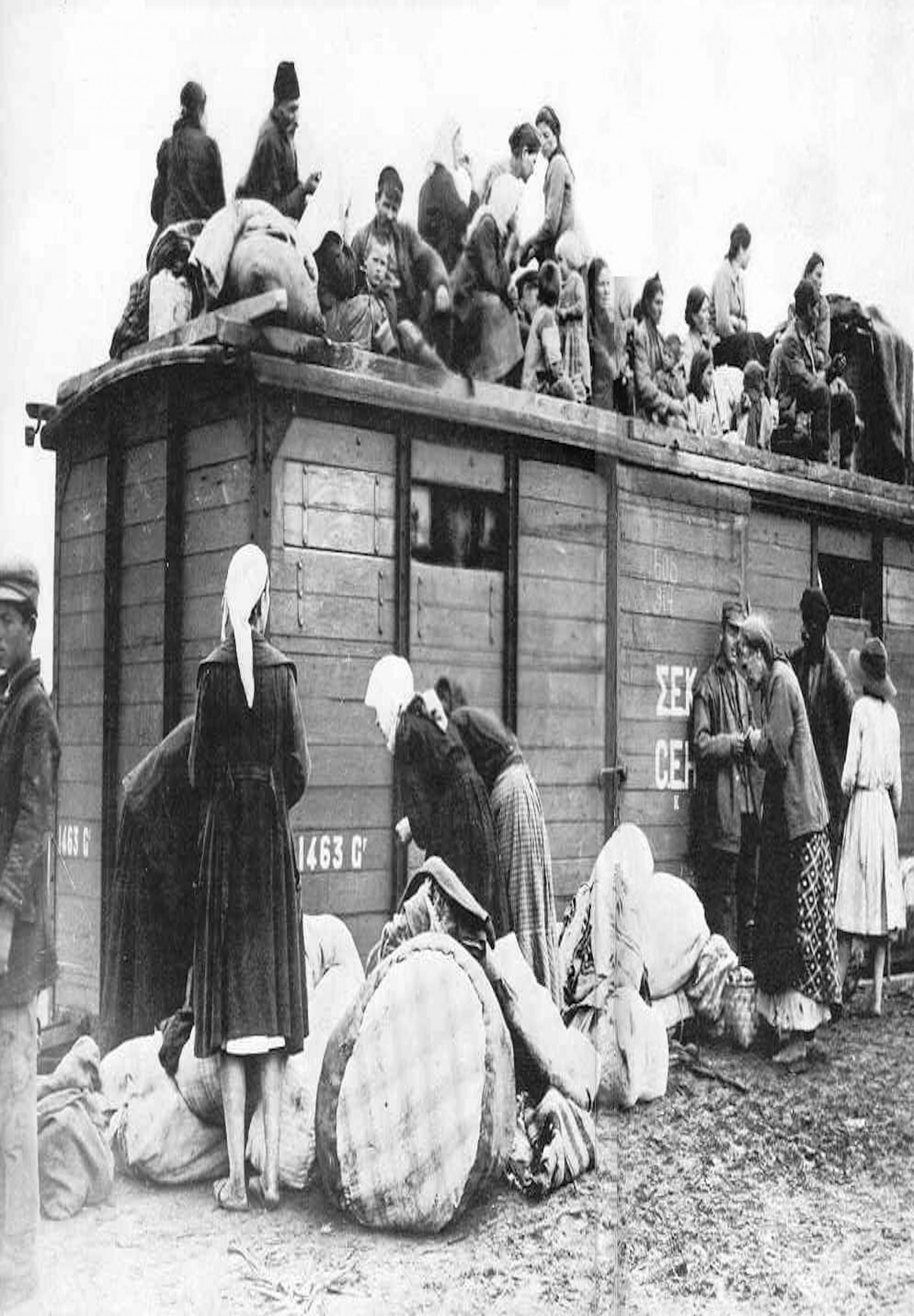

Conley Pace and his guide at last succeed in attaching themselves to a Greek cavalry detachment moving toward the front. Their advance, however, is slowed by enemy resistance near Arta. Then the battalion of infantry Pace and his guide join, the next day, itself has to flee at the report that the Greek army, advancing toward Ioannina, has been turned back by the Turks—and that 500 Circassian cavalry, reinforced by Albanian guerrillas, are sweeping toward them. Stumbling through dark foliage, with volleys of artillery landing behind them, gunfire whistling in their ears, and Greek (Epirian) refugees streaming alongside the sole escape route, Pace and his guide try to make their way back to Arta together with the retreating Greek forces. The Greek Guide is killed by shrapnel from an exploding shell, and Pace must slog on alone—trailed by the Guide’s corpse, slung across the back of a little gray pony.

Conley Pace is soon overtaken by a young Greek lieutenant, to whom he expresses his sorrow and awe at the sight of the refugees sweeping through the countryside, in flight from the threatening boom of Turkish artillery guns. So moved and inspired is Pace by the sights of war that not only does he volunteer to join the fight, but he also reveals to the lieutenant his real or true identity: Constantine Peza, a Greek by birth, not Conley Pace, his Anglicized name. Identifying with the Greek people and desiring to become directly involved in the fighting rather than merely observing it, Pace/Peza now begins a moral adventure that changes his feelings about the war, himself, and even the news business.

The young Greek lieutenant agrees to become Conley Pace/Constantine Peza’s guide into the war—hence into moral reflection, rather than journalistic correspondence. The contrast between these two characters foreshadows the difficulty Pace/Peza will have in his attempt to become involved in the fighting. The lieutenant finds the Greek-American’s fervent patriotism and heroic innocence at once amusing and contemptible. Although young like Pace/Peza, the junior-grade officer has already experienced battle and knows it is not the romantic adventure that the Greek-speaking foreigner imagines it to be. The lieutenant also knows that the Greek army—including Pace/Peza—is in retreat, not on the attack, so there will be little opportunity to confront and defeat the enemy. On the run, the lieutenant and Pace/Peza encounter little but the pitiable: wounded, exhausted, or feverish Greek soldiers and tired, hungry Epirian refugees.

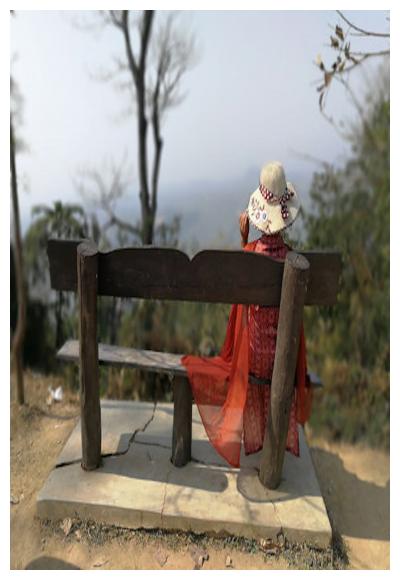

The next section of "Active Service", though not overtly concerned with Conley Pace/Constantine Peza, introduces a Greek child whose image—and question—will bring about Pace/Peza’s ultimate transformation. The child has been left behind by his parents in their rush to escape the Turkish advance. He plays tranquilly in front of his vacated little house, which is adjacent to the plain on which the fighting rages. Though the line of battle is moving imperceptibly closer, the boy shows only minimal interest in such action. It is too distant—and childish—an affair for one who, like him, is dealing intensely with sticks and pebbles in a pretend-game of sheepherding. Unlike Pace-Peza, who is now caught up in causes—in ideals and abstractions—the child commits himself to play that is direct, immediate, concrete.

"Active Service" then returns to Conley Pace/Constantine Peza as he further engages in the experience of war. Overwhelmed by the torrent of refugees and the stream of fatigued or injured soldiers on the road to Arta, Pace/Peza discovers that pity has its limits; he is now moved less by the sight of those in need than by the miracle of his own survival. He is also struck by the war’s failure to erase the commonness of familiar objects, such as poppies: an image of nature’s endurance in the midst of human upheaval. At this moment, the Greek lieutenant mysteriously, if not maliciously, parts company with Pace/Peza, leaving him alone and unguided to wander helplessly forward—unable to see the troops for the trees, as it were. When a shell shatters a nearby tree, Pace/Peza becomes astounded and bewildered at what he regards as the newfound vulnerability of the natural world.

When Conley Pace/Constantine Peza moves on to find a company of Greek artillery officers and soldiers as they hold the line (a trench-line), even in retreat, the men of this company more or less ignore him. Approaching the captain of the battery, Pace/Peza reasserts his Greekness and his desire to fight, even as a shell lands nearby yet does not detonate—much to Pace/Peza’s elation. As he climbs up toward a nearby artillery emplacement, Pace/Peza next encounters a soldier whose jaw is half blown away. Running from this “ghost,” Pace/Peza happens upon a squadron situated in another trench. From this vantage, he sees for the first time the Turkish battalions as they move steadily against the Greek defensive line, even as Greek artillery booms in response.

Fearing that the enemy will take the rear position he now occupies, Conley Pace Pace/Constantine Peza anxiously starts to run up and down the trench. Halting before a major, Pace/Peza announces his desire to fight for the fatherland. When the major instructs him to take a gun and some ammunition from a corpse, however, Pace/Peza shrinks back. Two soldiers perform the task for him, and Pace/Peza warily accepts the weapon and the bullets. Terrified, he then bolts for the rear, barely noticed by the Greek artillerymen—who get ready to combat the renewed Turkish onslaught.

At the beginning of the final section of "Active Service", the child reappears. Weary of his stick-and-pebble game and hungry, he finally realizes that he is all alone—above all, without his mother. The battle (or fighting retreat), now obviously closer, captures his attention for the first time, and he weeps at its incomprehensible mystery. Distracted by a nearby noise, the child sees something covered with dust and blood—Conley Pace/Constantine Peza—which is dragging itself up to the crest of a small hill, where it falls to the ground, panting. The child approaches Pace/Peza, looks into his eye, and asks a simple question: “Are you a man?” The question strikes at the heart of Pace/Peza’s dilemma, his attempt to define himself in relation to the Greco-Turkish War (if not New York journalism). As he gazes up into the child’s face, the boy repeats his question: “Are you a man?” But Pace/Peza can do nothing except gasp in the manner of a fish and put his head down, as the boy continues to stare at him.

Story & Logistics

Story Type:

Rite of Passage

Story Situation:

Daring enterprise

Story Conclusion:

Ambiguous

Linear Structure:

Linear

Moral Affections:

Duty, Penitence, Selfishness

Cast Size:

Many

Locations:

Many

Special Effects:

Minor cgi

Characters

Lead Role Ages:

Male Adult

Hero Type:

Ordinary

Villian Type:

Authority Figure

Stock Character Types:

Knight-errant, Miles Gloriosus

Advanced

Adaption:

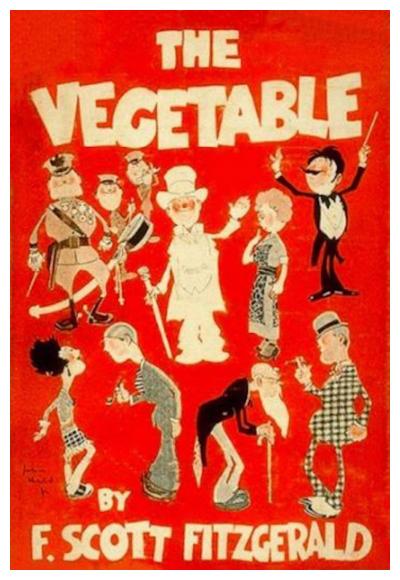

Based on Existing Fiction

Subgenre:

Action/Adventure, Anti-War, Epic, Expedition, Man vs Nature, Newspaper

Action Elements:

Physical Stunts, Vehicular Stunts, Weaponry

Equality & Diversity:

Diverse Cast

Life Topics:

Approaching Death, Mid-life Crisis/Middle Age

Super Powers:

Transportation and travel

Time Period:

Machine Age (1880–1945)

Country:

Greece, Turkey, United States of America (USA)

Time of Year:

Spring, Winter

Illness Topics:

Psychological

Relationship Topics:

Friendship (romantic)

Writer Style:

Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor, Dalton Trumbo, Terrence Malick