Synopsis/Details

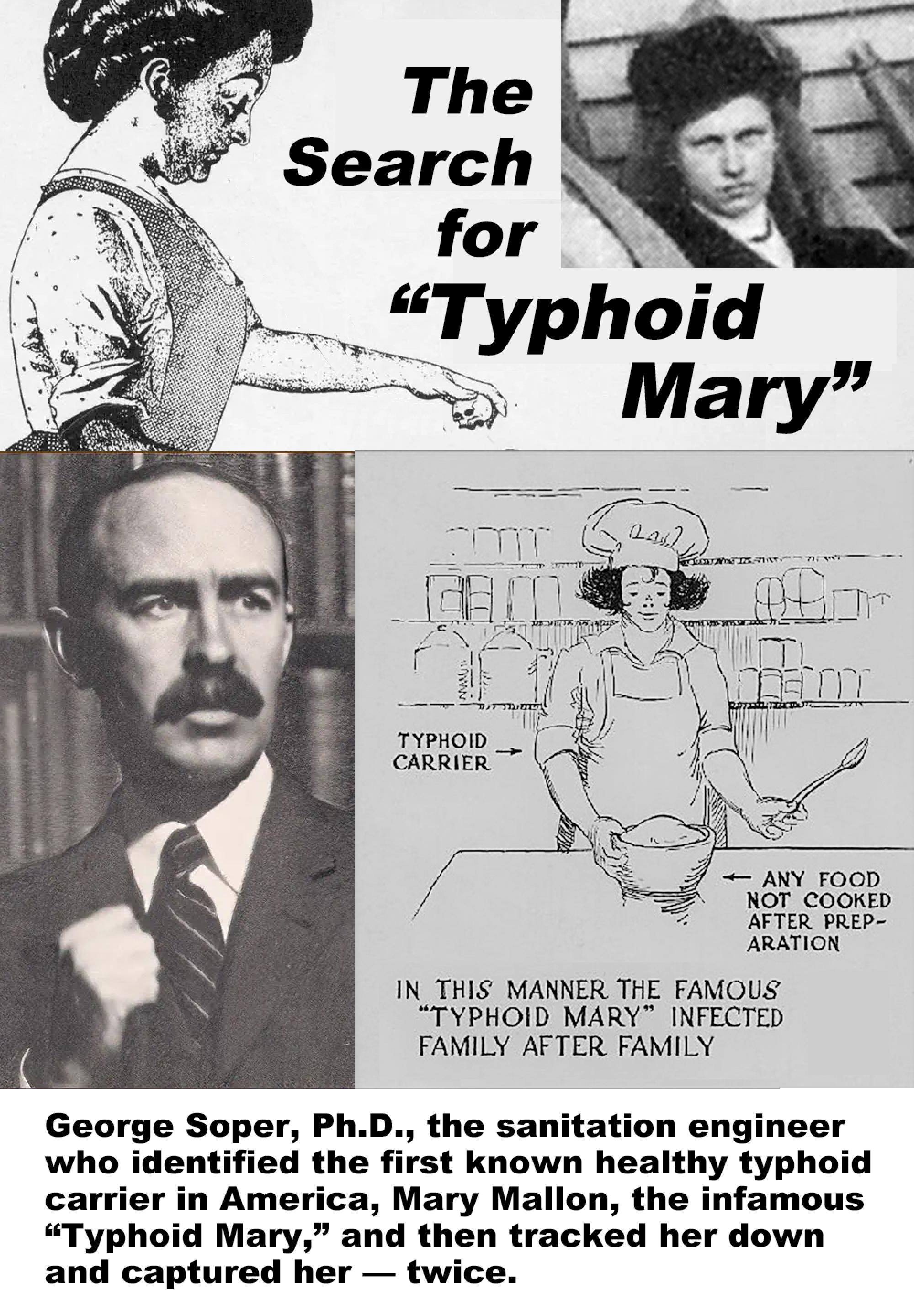

Mary Mallon (1869 – 1938), commonly known as Typhoid Mary, was an Irish-born American cook believed to have infected between 51 and 122 people with typhoid fever in the early 1900s, killing at least three and maybe as many as 50.

She was the first person in the United States identified as an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogenic Salmonella typhi. This was a virulent strain of bacteria carried in human feces and usually spread, city-wide, when crude sewer systems occasionally contaminated drinking-water supplies. The disease caused crippling socio-economic epidemics which laid up thousands for weeks, killing about 10 or 15 percent of the victims, mostly children and the elderly.

But the typhoid “carrier” state, eventually personified by Mary Mallon in America, was different; it was little known anywhere at the time and completely undiscovered in early 1900s America.

This script is less about Mary Mallon than it is about Dr. George A. Soper, the man who identified her as the first known American healthy typhoid carrier and then tracked her down and captured her — twice. How he discovered Mary and the carrier state in the U.S. is one of the great medical detective stories of all time, and Dr. Soper was not a physician but a Ph.D. in sanitary engineering.

In 1906 George Soper was asked to investigate, not a city-wide epidemic, but an isolated, household outbreak on Long Island that baffled the local authorities.

[Before continuing, the author, Will Soper, feels an explanatory note is necessary. I first stumbled upon Dr. Soper’s story when I was researching my Soper family tree. It turned out that George Soper is just one of the many distinguished Americans named Soper to whom I am not related.]

Because the usual sources of typhoid were absent in the Long Island case, Soper harked back to an obscure, ground-breaking German paper he had read recently. From a renowned researcher, Robert Koch, it indicated that about three percent of recovered, now completely healthy and immune, typhoid victims still harbored the germs and could pass them on to others. But for a carrier to “carry” typhoid to another it had to be “by hand,” that is, they had to prepare, manually, food that remained unheated before serving — and, then, only if they did not wash their hands after visiting the toilet!

Soper had learned that a new cook, Mary Mallon, had arrived in the family’s summer-house kitchen and prepared a favorite dish — sliced peaches pressed by hand into ice cream — three weeks before the outbreak, coinciding with the disease’s incubation period.

Of course, he wanted to speak with this Mary Mallon and have her examined, but she left shortly after the outbreak began. Soper learned that from 1900 until this Long Island placement in 1906, high-end domestic servant agencies had sent Mary Mallon as a cook to six families and five of them had typhoid outbreaks while she was there.

He visited a succession of employment agencies specializing in domestic help and finally got a tip she might be working at a large Park Avenue home. He arrived to find the young daughter very ill with typhoid and confronted Mary in the kitchen. There ensued a danse macabre exchange, with Soper, as tactfully as possible, telling her she was making people sick with typhoid and she denying she ever had typhoid (which can be very mild). Soper, of course, couldn’t expect to explain the carrier state of typhoid to her when he was the only person in America who knew that such a condition was possible.

“Mary,” he said, “General Warren called me to his summer house because I’ve worked on ending typhoid epidemics. And now that I’ve found you, well, there is typhoid here too — and there were at least 24 cases in five of your placements between 1900 and now.”

He paused to give her a chance to respond, but she didn't. She just looked at him furiously. “Mary, you carry the typhoid germs in your body and somehow infect others with them. I need your help in finding out how you do this, all the places you’ve done it, and what we can do to stop it. If you would be willing to submit voluntarily to some tests....”

Mary grabbed a large carving fork from the table and started toward Soper with it. He quickly exited and went to the health commissioner and got a judge to swear out an arrest warrant. It took five cops to subdue her.

She tested positive for typhoid and was confined to an isolation hospital for over two years. Then a new city health commissioner decided to free her, on the condition she report in regularly and never take another job preparing food for others. She violated this agreement almost immediately, taking cooking jobs, changing names, and eluding capture again for another five years. When Soper finally tracked her down this second time, she was working at a maternity hospital in Midtown Manhattan where she had sickened 25 in the staff cafeteria, killing two of them. This time she was put away for good, living out the last 23 years of her life in an isolation hospital.

The actual biological mechanism by which three per cent of recovered typhoid victims become asymptomatic carriers remained elusive for over a hundred years, until 2013, when researchers at Stanford finally solved the mystery.

Story & Logistics

Story Type:

Pursuit

Story Situation:

Pursuit

Story Conclusion:

Tragic

Linear Structure:

Non-linear

Moral Affections:

Accusation, Condemnation, Disapprobation, Scourge, Wrong

Cast Size:

Many

Locations:

Many

Characters

Lead Role Ages:

Female Adult, Female Middle Aged, Male Adult, Male Middle Aged, Male over 45

Hero Type:

Gifted

Villian Type:

Criminal

Stock Character Types:

Dark Lady, Everyman, Professor

Advanced

Adaption:

Based on True Events

Subgenre:

Autobiography/biography, Docu-drama, Drama, Historical, In Peril, Mysteries, Procedural, Social-Class, Social Commentary

Subculture:

High culture, Low culture

Action Elements:

Hand to Hand Combat, Physical Stunts

Equality & Diversity:

Female Protagonist, Immigration Focused, Income Inequality Focused, Minority Protagonist

Life Topics:

Death, Near Death Experience

Time Period:

Machine Age (1880–1945)

Country:

United States of America (USA)

Time of Year:

Summer, Winter

Illness Topics:

Physical

Relationship Topics:

Bonding, Boyfriend, By marriage, Girlfriend, Significant other

Writer Style:

Dalton Trumbo, Oliver Stone