Synopsis/Details

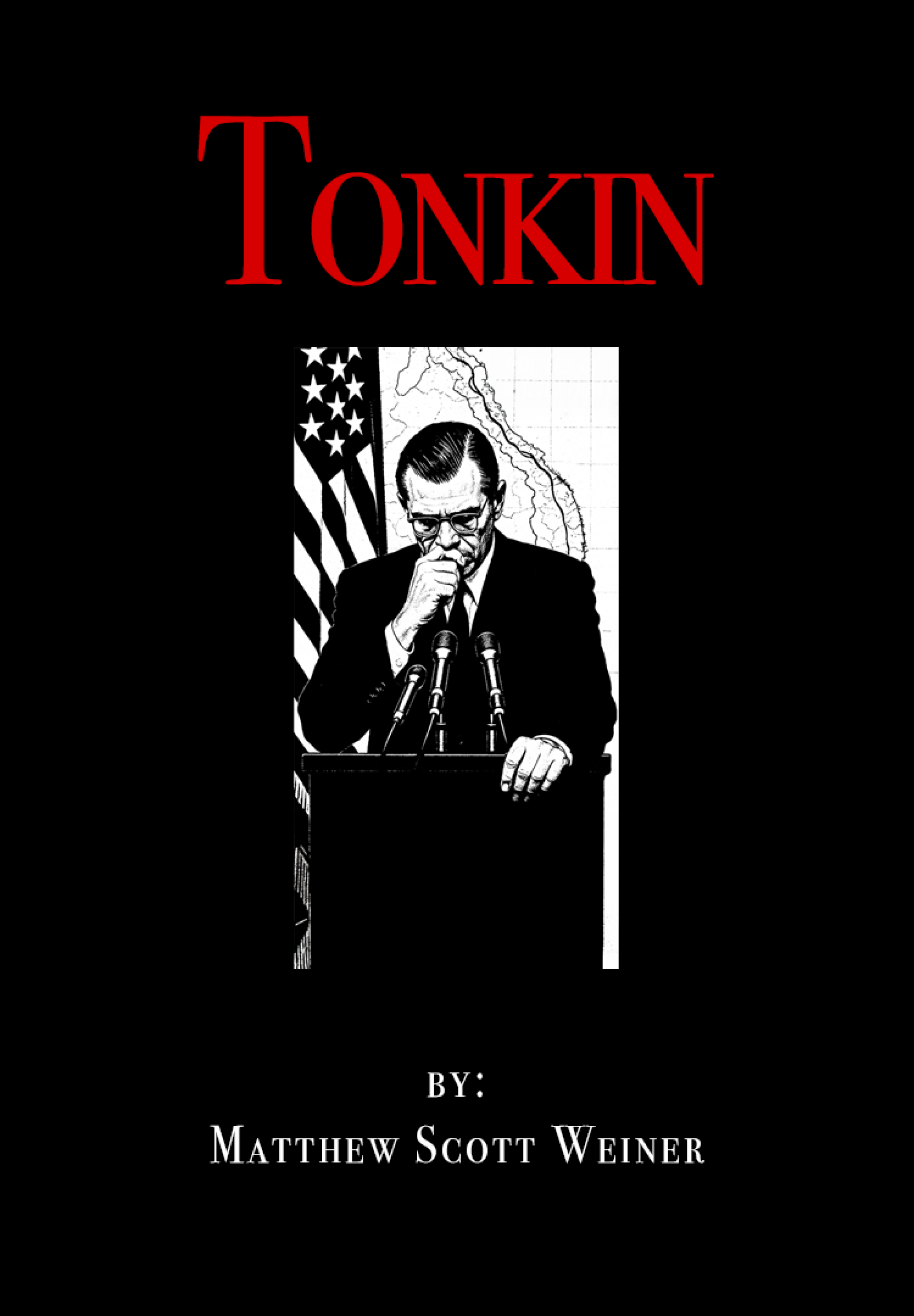

Robert McNamara begins his days weighing ants on his patio tiles and ends them shaping the fate of nations. Far from morning calm, covert South Vietnamese raids orchestrated by U.S. planners strike North Vietnamese radar posts, prompting the USS Maddox into contested waters. Captain Herrick, monitoring intercepted threats as fishing junks drift like floating mines, speeds toward international waters with Commander Ogier and Lieutenant Moore braced for conflict. When three PT boats charge through the chop, Maddox responds—guns thunder, torpedoes miss, and overhead, Crusader jets chase the attackers away.

Word of the engagement races across the globe, waking McNamara by red-phone ring and triggering a cascade of decisions where family breakfast intersects with war planning.

In the Oval Office, President Lyndon Johnson wrestles humor and dread beneath JFK’s bust. Advisors offer competing counsel: Dean Rusk calls for strong retaliation, General Wheeler demands force, and McGeorge Bundy balances politics and principle. McNamara publicly urges caution but privately recommends bolstering presence with another destroyer, Turner Joy, and a diplomatic note to Hanoi—tempting a second strike to justify escalation.

On Capitol Hill, Senator Wayne Morse grills McNamara on territorial waters and covert operations. McNamara deflects with icy statistics, maintaining control. At home, teenage Craig McNamara questions his father over bacon and Beatles records, sensing contradictions behind polished logic. Marg McNamara watches silently, troubled by how secrecy has eroded her husband’s ease.

The second night in the Gulf brings more confusion than clarity. Radar screens bloom with phantom blips, sonar pings echo imagined threats, and storm-wracked seas distort perception. On USS Constellation, air crews launch Skyhawks into blackness, flares reveal no enemy, and frustration replaces certainty. Everett Alvarez, eager for real combat, returns from a fruitless sortie to an admiral demanding proof that no one can offer.

Captain Herrick’s post-action cable expresses doubt that any second attack occurred. But McNamara personally calls, pressing for confirmation to solidify the narrative. By dawn, he assures Johnson of certainty, and the Tonkin Resolution blueprint is ready.

Everett Alvarez’s wish for combat arrives with Operation Pierce Arrow. Briefed on a North Vietnamese torpedo-boat base at Hon Gai, he launches alongside Nick Nicholson and Ronnie Boch under clear skies. Rockets strafe the bay, machine guns rake patrol craft, and black flak rises in reply. A shell tears through Alvarez’s Skyhawk; controls freeze, smoke fills the cockpit, and he ejects into the Gulf.

Fishermen drag him from the water, strip him of gear, and hand him to militia. He’s paraded through cheering crowds chanting “Mê! Mê!” and bound beneath a tarpaulin aboard a torpedo boat. At Hoa Lo prison, an elderly interrogator rattles off facts about Alvarez’s life with eerie precision. He gives only name, rank, and serial number, clinging to protocol as leg irons clamp down and a mosquito net trembles above.

Back in Washington, Johnson addresses the nation from the Fish Room. Flanked by McNamara, Bundy, Wheeler, and Rusk, he announces that repeated aggression demands “positive reply.” Air strikes are already underway. Families lean toward flickering screens. Marg McNamara slips away quietly; Craig watches, absorbed by the cadence of war. In Mississippi, three murdered civil rights workers cast a pall over the broadcast, reminding Johnson of human cruelty and courage. He confides in McNamara, who silently absorbs it, eyes drifting again to Kennedy’s bust and moon photos from Ranger 7.

Government machinery accelerates. Congressional leaders pack the Cabinet Room. Senator Richard Russell pushes for an expanded fight. Speaker McCormack promises swift passage. Only Morse stands in opposition. Over pie in an Arlington diner, Morse warns McNamara that public trust cannot survive concealed provocations. McNamara responds with the cool confidence of one who believes mastery and boldness will deliver victory. Morse casts a lonely “no.” The House votes 416-0; the Senate, 88-2, handing Johnson sweeping powers “like grandma’s nightshirt—able to cover everything.”

Back home, ants return to McNamara’s patio, undisturbed by geopolitics. Inside, Marg asks whether the captured pilot troubles him. His cold “no” chills the air, revealing how forty-thousand-foot judgments have numbed personal concern. Captain Herrick replays transmissions, haunted by how doubt became reportable fact. In Hoa Lo, Alvarez endures interrogations, forced mapping, and brutal transport deeper into the prison system.

Johnson relishes the legislative victory but mutters, “Now all we have to do is win a war,” to which McNamara replies, “That’s what you have me for.”

The final montage captures overwhelming congressional support, the war that followed, and Everett Alvarez’s near-nine-year captivity. Moon craters and ants, family breakfasts and prison cells, linger in memory—echoes of McNamara’s personal arithmetic. Every decision begins with measuring loss, yet some losses prove incalculable. As night falls, ants advance across patio tiles once more, indifferent to war, resolutions, and speeches, while distant thunder over the Gulf of Tonkin fades into history.