Synopsis/Details

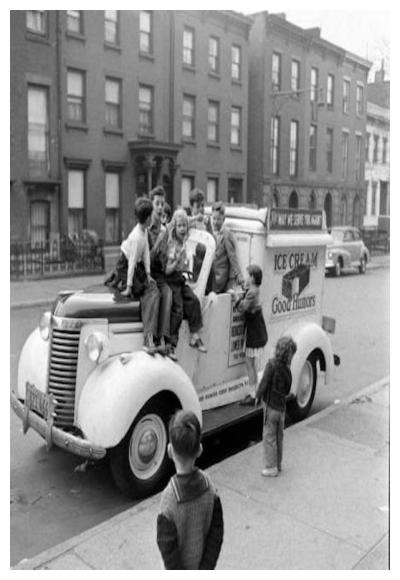

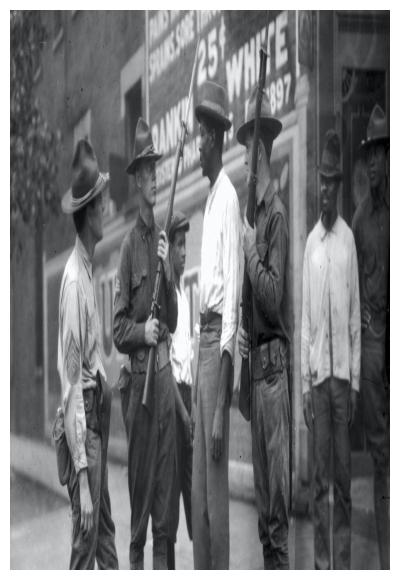

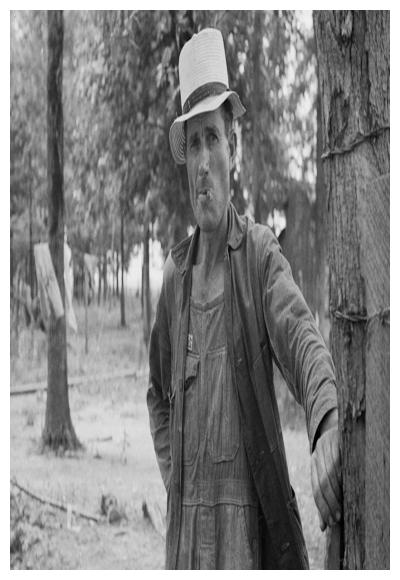

This script opens with two Irish policemen comparing their experiences working the tough streets on the Lower West Side of Manhattan in 1915. They come upon a downtrodden, impoverished old man (the ragpicker of the title) as he rummages through trash cans for bottles, cans, and tin to sell—at the same time as he is shunned by people on the street who just go about their business. When the old man himself ignores an old woman’s offer of a coat, she turns to others for help rather than taking action herself. She thinks that somebody should “do something”; she represents those Good Samaritans who preach reform but pass on the responsibility for action to others. A grocery boy’s subsequent implication that the old woman should forget about the old man represents Americans at their most apathetic, if not antipathic. For their part, children walking home from school ridicule the ragpicker, and thereby suggest that human beings’ prejudices are carried from generation to the other.

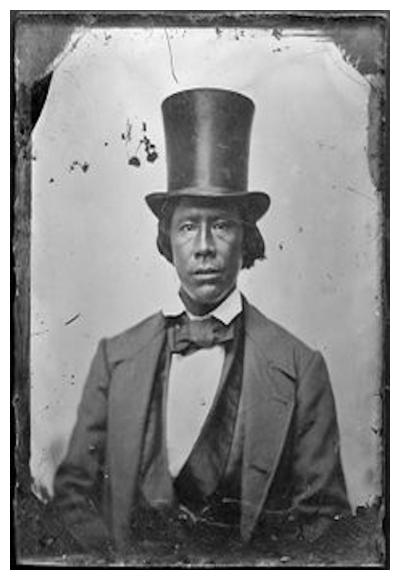

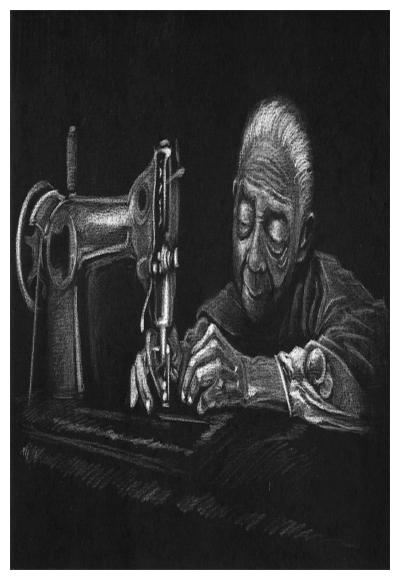

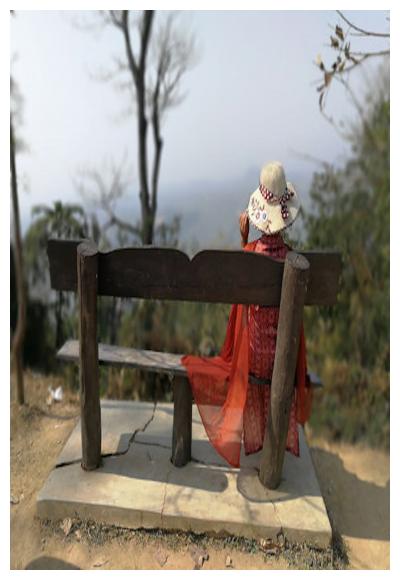

Lost in his past, the ragpicker rambles on to the two police officers, and we soon discover that he was once a powerful man. A former capitalist, he has lost his money, his wife, his child, his friends, and finally his identity—all as a consequence of the play of economic forces. Despite his losses, the ragpicker, in his madness, has achieved a certain acceptance of his fate and an inner peace. “I’m not crazy now,” he mumbles. “I got better . . . I live by myself now. I’m all alone where I can watch the water go by and the boats and the clouds.” Ironically, although he cannot remember his name when the two cops prod him, the old man seizes upon the taunts of a passing streetboy, who calls him a “ragpicker,” to muse, “Ragpicker! Ragpicker! . . . Now I remember. That’s my name.”

"The Ragpicker" is thus a compassionate study of a homeless man as he forages on the street for sustenance and respect, as well as to bury his sorrows. "The Ragpicker" wants readers/viewers to put aside their distaste for the slovenly appearance and disquieting activity of the “bum” who inhabits its pages. Readers/viewers are asked instead to weep for this old man because, in forgetting his own name, he has lost his dignity—yet struggles to rediscover it. They are not asked to pity the decline the ragpicker has suffered in going from riches to rags, for he himself ignores the pitying offer of the coat and other assistance. The ragpicker himself asks merely that people not throw tin cans at him; that they respect his desire to remain alone, to make his own determination of what will suffice for his subsistence; that they allow him the mere pleasure of seeing, and sensing, the passing water, the boats, the clouds.

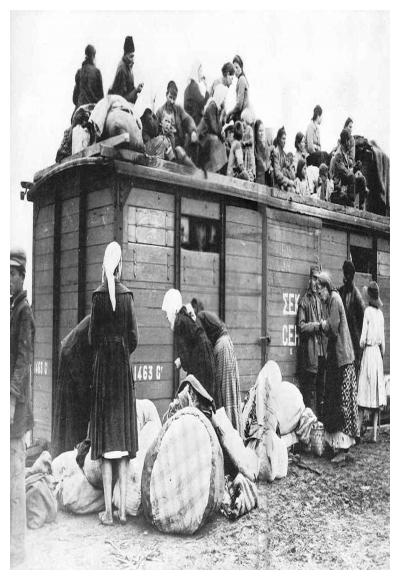

On the one hand, "The Ragpicker" is an age-old indictment of callous attitudes toward the poor and a bitter comment on the irony of fate. On the other hand, this script portrays one human being as the archetypal, helpless victim of mechanistic forces in a world that is amoral; in doing so, "The Ragpicker" maintains a kind of heartless balance between those who succeed, like capitalists, and those who fail, like the old man. That such a work has distinct (and heartfelt) relevance to our own age—what could be called the age of homelessness, migrancy, even elder-abuse—should go without saying.

Story & Logistics

Story Type:

Road Trip

Story Situation:

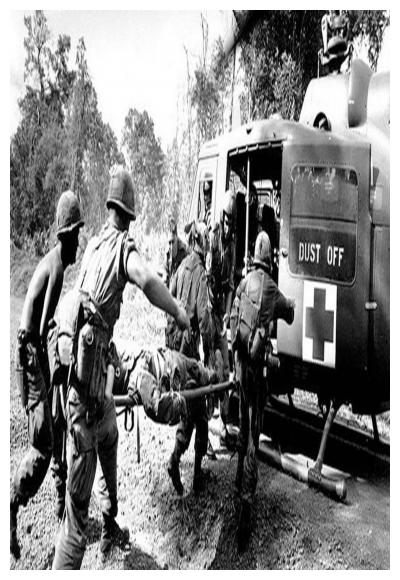

Falling prey to cruelty/misfortune

Story Conclusion:

Sad

Linear Structure:

Linear

Moral Affections:

Scourge

Cast Size:

Many

Locations:

Single

Special Effects:

Minor cgi

Characters

Lead Role Ages:

Male over 45

Hero Type:

Unfortunate

Villian Type:

Authority Figure

Stock Character Types:

Wise fool

Advanced

Adaption:

Based on Existing Fiction

Subgenre:

Disease/Disability, Man vs Nature, Social Commentary, Social Problem, Survival

Subculture:

Bohemianism

Action Elements:

Physical Stunts

Equality & Diversity:

Elderly Protagonist

Life Topics:

The Elderly

Drug Topics:

Rehabilitation

Super Powers:

Physical or mental domination

Time Period:

Age of Oil (after 1901)

Country:

United States of America (USA)

Time of Year:

Winter

Illness Topics:

Psychological

Relationship Topics:

Abuse, Elderly

Writer Style:

Horton Foote, Sidney Howard, Waldo Salt